Btrax Design Company > Freshtrax > The Matcha Myst...

The Matcha Mystery: Why Your “Japanese” Matcha Might Be Made in China

During a meeting earlier this month with Brandon Hill, CEO of btrax, our conversation shifted from sales and marketing to Japanese culture and business practices. We somehow landed on matcha, and he told me about a video he’d recently seen saying, “You know, some Chinese matcha brands are deliberately misleading consumers into thinking they’re buying Japanese products.”

This sent me down a rabbit hole. How widespread is this practice? What’s the impact on consumers? And what does it say about how products cross cultural boundaries in our globalized market?

The phenomenon is more widespread than you might think. A significant number of matcha products featuring Japanese-style branding are actually produced in China. Brandon was onto something as it looks to be a trend that reveals fascinating insights about global supply chains, consumer psychology, and the evolving tea industry.

The Plot Twist: China Returns to Its Roots

Here’s a fun fact that might surprise you: powdered tea actually originated in China during the Tang and Song dynasties. It was monk Eisai who introduced this practice to Japan in the 12th century, where it evolved into the ceremonial matcha culture we know today.

Fast forward to today, and China has re-entered the matcha game in a big way. But unlike the ceremonial traditions that flourished in Japan, Chinese matcha production is primarily focused on meeting industrial-scale demand, think smoothie bars, bakeries, and food manufacturers worldwide.

The Production Process: Two Different Worlds

When it comes to how matcha is made, Japanese and Chinese producers take dramatically different approaches:

Japanese Matcha:

- Plants are carefully shaded for 2-4 weeks before harvest to boost chlorophyll and L-theanine (that’s what gives you that yummy umami flavor)

- Leaves are steamed immediately after harvest to stop oxidation

- Traditional stone-grinding produces that ultra-fine powder

Chinese Matcha:

- Shading is uncommon, resulting in less chlorophyll and more bitterness

- Leaves are often pan-fired, giving a roasted note and duller color

- Milling can vary from machine grinding to hand-grinding

Why It Matters: More Than Just a Name

For traditional Japanese tea producers, this goes beyond market competition, it’s about cultural integrity and consumer trust. Legal experts warn that even under Chinese law, misleading use of brand names could violate laws concerning origin labeling and brand misrepresentation if consumers believe they’re buying products made in Kyoto.

But taking legal action remains challenging. There are multiple companies in China marketing matcha under the Uji name, each requiring individual lawsuits. The combination of legal costs, jurisdictional hurdles, and limited protection for unregistered foreign trademarks in China makes enforcement nearly impossible for Japanese firms.

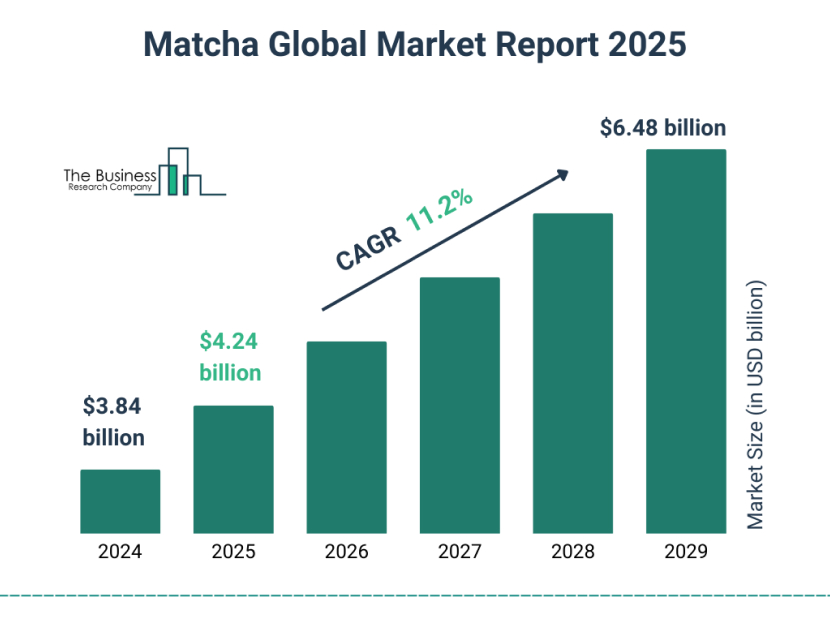

As the global matcha market is projected to grow to over $6 billion by 2033, the stakes are rising. China has become the largest matcha producer by volume, exporting to over 40 countries, while Japan maintains its position as the leader in ceremonial and premium matcha.

But here’s what really makes this a business story worth following: the Chinese company behind the Marukyu Koyamaen imitations claims they began operations in 2006 with the goal of “reviving Chinese traditions of powdered tea.” Their website displays a statement suggesting they’re supported by tea masters from Kyoto and have introduced equipment and techniques from Japan. Sound familiar? It’s the same pattern we see in other industries where cultural heritage becomes a market advantage.

This image shows shipping boxes labeled “Uji Matcha” (宇治抹茶) stacked on pallets outside a facility in China. Despite being produced by a company called Yuzhi Matcha (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., the packaging prominently uses the name of Uji, a region in Kyoto, Japan, renowned for its high-quality matcha. The boxes also include misleading phrases such as “Supervised by Japan Uji Matcha Co., Ltd.,” creating the appearance of a direct connection to Japanese producers. This visual highlights the scale and intent behind the controversial branding, raising serious concerns about origin misrepresentation in international tea distribution.

The Real Deal: When Tradition Meets Imitation

Here’s where Brandon’s observation really makes sense. Many Chinese matcha brands adopt Japanese aesthetics in their brand names, packaging, and advertising materials. Sometimes this practice extends beyond general cultural borrowing.

Take Marukyu Koyamaen, a traditional tea maker in Kyoto dating back to the Edo period. This company has spent generations building its reputation for premium Uji matcha, with signature products like “Seiran” and “Wakae” that have become quite sought after.

Recently, they discovered Chinese companies selling matcha online using these exact same product names and packaging designs, marketing them as “Uji matcha” – despite being manufactured in Shanghai. The president of Marukyu Koyamaen, Koyama, expressed his concern: “To have our tea, nurtured with such care, used in this way is concerning.”

The differences are noticeable. While the authentic Kyoto matcha displays a deep green hue with rich flavor, the Chinese versions had a more muted appearance and lacked the characteristic bitterness and aroma that distinguish genuine Uji matcha.

The Legal Gray Area

This isn’t just casual cultural borrowing – it’s strategic positioning that exploits legal loopholes. Chinese matcha producers face skepticism in their own domestic market because consumers expect authentic matcha to be Japanese. As a result, some Chinese brands actively avoid promoting their Chinese origin, instead doubling down on Japanese-style branding.

The Chinese company behind the Marukyu Koyamaen imitations acknowledged using “Uji matcha” and even a slightly altered “Oji matcha” on their products. When confronted by the Japanese press, they denied any intent to deceive, claiming, “We’ve completed all procedures properly. We don’t see how this could mislead consumers.” Their website even suggests they’re supported by tea masters from Kyoto and have introduced Japanese equipment and techniques.

The most surprising part? Unlike Champagne or Parma ham, matcha has no protected designation of origin status internationally. Even more concerning, terms like “Uji matcha” remain unprotected under Chinese trademark law, creating a legal loophole that Chinese producers freely exploit.

While “matcha” itself is a generic product term, “Uji” specifically refers to a prestigious region in Kyoto that has been Japan’s premier ceremonial tea-producing area for centuries. Geographic Indications (GIs) that protect place names like the ironclad protections enjoyed by Champagne require formal international registration and rigorous enforcement mechanisms that Uji currently lacks. So while these labeling practices may be technically legal, they represent a profound form of consumer deception, particularly for tea enthusiasts seeking authentic Japanese products with genuine cultural heritage and superior quality standards.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

Here’s what the global tea trade looks like today:

- China is now the largest matcha producer by volume, exporting to over 40 countries

- Japan maintains its position as the leader in ceremonial and premium matcha, commanding higher export values per kilogram

- The global matcha market is projected to grow to over $6 billion by 2033, with China filling much of the supply for industrial and foodservice applications

Smart Shopping: What to Look For

If you’re in the market for matcha and want to make sure you’re getting what you expect, here are some practical tips:

- Check the country of origin: Not just the brand name or packaging design. Look closely at the fine print.

- Be skeptical of “Uji matcha” at suspiciously low prices: Authentic Uji matcha from Kyoto commands premium prices for good reason.

- Ask about production methods: Was it shade grown? Steamed or pan-fired? Stone-milled or machine-ground?

- Consider your intended use: Are you buying matcha for a traditional tea ceremony, or for your morning latte? Different grades serve different purposes.

- Look beyond the Japanese style branding: Companies are getting sophisticated about using kanji, Japanese-sounding names, and even claims of “collaboration with Kyoto tea masters.”

The Bigger Picture: A Case Study in Cultural Commerce

The Marukyu Koyamaen situation perfectly illustrates what we’re seeing across various product categories where country of origin signals quality or authenticity. Just as Toyota had to adapt to succeed in the U.S., we’re now witnessing Chinese producers not just adapting to, but actively co-opting Japanese cultural cachet.

When Toyota entered the U.S. market in the late 1950s, its early efforts stumbled, cars like Toyota’s Toyopet Crown were considered underpowered and poorly suited to American driving preferences. But instead of mimicking American brands or misleading consumers, Toyota leaned into its Japanese identity while carefully adapting to local market expectations. It re-engineered its products, launched U.S.-specific models like the Camry, and even introduced Lexus, a brand built from the ground up to reflect Western notions of luxury. Over time, Toyota earned its place as a trusted name in American households through strategic localization, manufacturing investments in the U.S., and an authentic emphasis on quality rooted in Japanese craftsmanship.

This stands in sharp contrast to what’s unfolding in the global matcha market, where certain producers are not celebrating their own origins, but instead borrowing the cultural symbols of another, namely Japan’s. The fact that Chinese matcha producers feel compelled to use Japanese aesthetics, regional names like “Uji,” and even suggest Kyoto-based partnerships speaks to the significant market value carried by the “Made in Japan” label.

This isn’t just happening in tea. Across other industries, there are similar efforts to leverage cultural perception:

- In beauty, Korean companies like Missha release products branded as “Missha Paris” to capitalize on French luxury associations.

- Trader Joe’s offers “Sakura Mochi” and “Miso Ramen” under Japanese-sounding labels, though the products are often made outside Japan and adapted for American palates.

- Nike and others have drawn criticism for borrowing Japanese cultural markers, like “Kimono” branding, without respecting their significance.

As one expert noted, without urgent countermeasures, products labeled “Uji matcha” may continue circulating far from Kyoto, undermining the integrity of a cherished cultural symbol. It raises important questions about transparency, consumer expectations, and how cultural heritage translates into market value.

The key for consumers is awareness. Whether you’re dropping $60 on ceremonial-grade matcha or grabbing a $12 bag for smoothies, what matters is knowing what you’re getting and why. At the end of the day, your choice should be informed, not influenced by strategic packaging designed to play on cultural associations.

From Mismatch to Match: Why Cultural Context Matters

Navigating global markets today isn’t just about translating words, it’s about translating meaning. The matcha mislabeling issue is just one example of how cultural context, brand trust, and consumer perception intersect in powerful (and sometimes problematic) ways. Whether you’re launching a product in Japan, adapting your brand for U.S. audiences, or expanding across Asia, success depends on more than just surface-level localization.

What We do

At btrax, we specialize in helping companies authentically enter and grow in markets like Japan and beyond. From brand strategy and user research to marketing execution and cross-cultural design, our team bridges East and West to ensure your message resonates and your brand earns trust.

Thinking of entering the Japanese market? Let’s make sure your brand story resonates, not just translates. Contact us HERE